Archive for May, 2011

Interactive Fiction (part 2)

I decided to clean up and refactor the code some from part one, although it still works the same way: we still have behaviors that various objects can become. I’m not going to go through every part of the code, but I will talk about how behaviors are designed, explain the parser, how commands are handled, and how a prop (the lamp) is implemented.

Behaviors

First, here’s how you create a behavior:

Something = behavior() function Something.methods.whatever(self) ... end

Interactive Fiction (part 1)

Like it or hate it, and there are plenty of reasons to do both, object-oriented programming is an idea that you can’t escape. Practically every language and every library uses it. Every CS curriculum teaches it. Every learn-to-program tutorial explains it. And so, people have some funny ideas about what it exactly is. If your first language supports it (like Java or Ruby, say) then it becomes very hard to distinguish between object-oriented programming and how your language does object-oriented programming.

Unless you’re using Lua. Because OO in Lua is whatever you write for it. The language doesn’t offer any of what a Java programmer would consider essential features, like classes, instance variables, even types. What it offers is a way to make those things. So that’s what I’m going to do over the next couple posts, in the process of writing a miniature interactive fiction engine. At the end it’ll look a little bit like this except that I’m going to make a bunch of compromises that Zarf never would, because he’s smarter than I am and can foresee how it’ll mess everything up. Also because he intends to use his for longer than a blog post.

Read the rest of this entry »

Enumerating All Trees

This is a problem in The Art of Computer Programming volume 4A, which only came out a few months ago. My solution isn’t Knuth’s solution, mostly because I don’t understand Knuth’s solution, but it works and it’s fairly easy to explain.

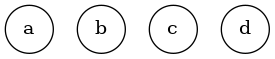

The problem is this: given a number of nodes (like, say, 4), generate every possible arrangement of those nodes into a tree. So this is one:

() () () ()

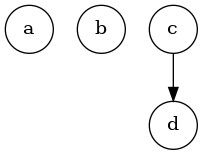

This is another one:

() () (())

And so on. For n nodes there are 2n-1 possible trees. And it’s not immediately obvious how to generate them.

Read the rest of this entry »

Generating Heightmaps in Lua

Lua is a pretty much ideal language for playing around with map generating functions. I made a cute one today, combining linear noise with a couple other things.

To start off with, here’s how I create a Lua map class: I start by making a “Map” table that contains a “methods” table. Anything class-level (what Java would call “static”) goes in Map; anything instance-level goes is Map.methods. I make a Map.new function that creates a new Map of a certain size, filling it with either a constant value or linear noise (I’m using 16 elevation levels):

Map = {methods={}} -- Make a grid of random values 0..15, or a fill value function Map.new(width, height, fill) local map = {width=width, height=height} setmetatable(map,{__index=Map.methods}) for n = 1, (width * height) do map[n] = fill or (math.random(16) - 1) end return map end

Pretty basic so far. I’ll add a few methods like at and set that change values based on x and y coordinates.

Convenient Lua Features: package.preload

Lua is designed for embedding into larger host programs. Last time I talked about how to make C functions available to Lua, now I want to talk about how to bundle Lua libraries in with your host program.

First, we have to understand what it means to load a library. Most Lua libraries are packaged into modules (which I’ll get into later), one module per file. You call require and pass it a module name, and it returns the module (usually as a table containing some functions).

Notably, you’re not passing a file name to require, you’re passing a module name. The fact that these modules map to files is just sort of coincidence. In actuality, require looks in several different places (locations on package.path, C libraries on package.cpath, and so on) for a function that will evaluate to the module.

A function that evaluates to a module is called a loader. Searchers try to find loaders, so there’s a searcher that looks in files and returns functions that call dofile on them, for example. Each searcher that Lua uses is stored in the confusingly-named package.loaders, so one way to find this would be to add a searcher that will look for a particularly-named function (exposed from C) and call it, like if I try to load “foo” that means try to call “load_foo_from_c()“.

But, even before it starts calling searchers, it checks if you’ve provided a loader for that module by hand. You can do that by putting it in a table, package.preload. If you only want one module this is much easier to do.

Tying C to Lua

I wanted to write something about Lua’s C interface, but I couldn’t think of anything good and self-contained with my Cocoa Lua stuff (part of the point of using notifications is that I don’t have to do much C interface stuff) so I figured, I’ll write a tiny tile-based map thing.

Let’s say you want to write a game in Lua, and you want to have a really gigantic map. Storing it as a Lua table would be a little unwieldy, especially if you want to do things like run functions over it for map generation (fractal map generation, smoothing, whatever). It would be really nice to write that in C and have some basic functions in Lua to access it. So, we’re going to write a function that creates a map of a certain size, and another one that returns (as a table) a rectangular “slice” of the map:

map = Map.create(256, 256) Map.slice(map, 256, 100, 100, 15, 15) -- map_width, x, y, width, height

Uncommon Lua Features: Coroutines

Last week I talked about how to use Cocoa notifications to connect a Lua environment to a Cocoa UI. This is great for things like this:

When the user clicks a space on the map containing a unit, update the status panel with the specs for that unit

But terrible for things like this:

When the user clicks OK, load the next level out of the level file and send it to a Lua function for pre-processing

Things like that are even more common than the first type, but result in terrible code. What to do?

Handling Cocoa Notifications With Lua

This is less a “cool Lua trick” and more a “cool way to use Lua”. What I’m doing is using Lua to write a Cocoa application. There are a couple tools to do this (Wax and LuaCore spring to mind) but they work on a different paradigm: they’re like RubyCocoa in that they have a bridge where you can write Lua code that makes Cocoa objects, and write your whole app in Lua. I don’t want to do that because I don’t want to get in a race with Apple. Cocoa has a pretty good Objective C interface, including stuff like blocks and Interface Builder and CoreAnimation, and I’m perfectly happy to use it. I would just prefer to write the parts of my program that aren’t tied to Cocoa objects in something a little more terse.

Making Lua Look Like Prolog

Lua, like most languages, has some object-oriented pieces. But, it doesn’t have classes and modules and objects: it takes the Scheme approach and gives you the tools you need to build the OO paradigm you want to use. In particular, the only data structure it gives you is called a table and is essentially a hashtable married to an array (it’s a hashtable, but it has accelerated access for integer keys, so it’s efficient to use for either one). Tables can be assigned metatables which define special behavior for the table: if you try to access a key that doesn’t exist, it looks in the metatable for “__index” and uses that to find what the value should be.

But if all that was intended was to make it easy to duplicate class-based OO, Lua would just have put in class-based OO, right? Let’s try something different, that uses this same trick to do something cool. Let’s make Lua look like Prolog.